I’ve been playing around with FoxyTunes, installing it in Firefox, getting the TwittyTunes extension. And it’s not just because I like music. I think what’s happening here is very powerful.

Let’s start with Twitter, it looks harmless and gormless, what possible use could it have? After all, what can you do in 140 characters? Let’s see.

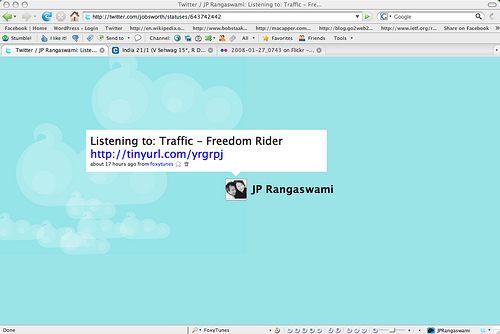

First off, I can send messages that look like the one below. I typed it in myself, it described what I was doing at the time.

What don’t I like about it? Well, it’s not good enough for the 21st century. For starters, I shouldn’t have to type it in. Something should be scraping what I am doing, capturing it in a way I can choose to share with others. Choose, we must remember that word. And what else? Oh yes, wouldn’t it be nice if I could enrich the information I was sending? Provide more information about the artist or group, maybe YouTube video links, maybe Wikipedia links, maybe Flickr links, maybe even the homepage of the band or group. How about a link to the song itself, so that someone else can sample it, try it out, decide for themselves if they like it? Maybe even a way to search for more information, and the tools to buy the CD or DVD in physical or digital format?

Chance would be a fine thing, but ….. how can I SMS all that? But wait a minute, the 140 character limit isn’t a real limit, not if I send a short url linking to all that. Or even better, having someone do that for me, a web service like tinyurl.

So now all I need is for someone to build an app that scrapes what I am listening to, figures out what it is, goes and collects the enrichments and conveniences I want to send with the information (band links, YouTube, Flickr, Google, Amazon, the Facebook fan page, maybe a Netvibes collection of related feeds, the Wikipedia entry and so on) and then packages all that into a small space using something like tinyurl.

Which brings me to TwittyTunes and FoxyTunes. Now my Twitter message looks like this:

It does the scraping, directly out of my iTunes. It lets me choose whether to share what I am listening to with others, song by song. It sends the message on to Twitter. But that’s not where the value is. For that, you, the “follower” of my tweet, need to click on the link, and hey presto, you get something that looks like this:

You see, this is why I play with things like Twitter. Not because I want to appear cool. But because I am so old and grey and slow that the best way I learn is by playing. Now I can really see how something like Twitter can add value in the enterprise. And I’m secure enough in myself to want to share what I find out, openly and freely. Which is what I’m doing here. [Without a business model or a monetisation plan in sight :-)]

It’s worth bearing a few things in mind. First there was the web. Then there was SMS. Without SMS there is no Twitter. Without the web there is no Twitter. Now we’ve had tinyurl for a long time, but it starts coming into its own when we start using something like Twitter. As a result of all this, someone else could build something like FoxyTunes (which looks like Netvibes meeting last.fm), and then building TwittyTunes to connect up with the Twitter world. And then suddenly everything else waltzes in to enrich what we can see and do, ranging from text to audio to video, from search and syndication and conversation to fulfilment.

What strikes me is the power manifest here, the power of connecting simple things like SMS and tinyurl and Twitter. Small pieces loosely joined, as David Weinberger said.

We are moving into a world where open multisided platforms will dominate, with simple standards and simple tools connecting up wide open spaces. We are seeing it happen now. This post is not about FoxyTunes. Or TwittyTunes. Twitter. Or Facebook. Or Google. Or Amazon. Or iTunes. Or Flickr. Or YouTube.

It’s about all of them. It’s about all of them, and the apps we don’t know about yet, the ones that will emerge tomorrow. How we can find ways of bringing all of them together and moving information around them, linking information between them, enriching and sharing that information beyond them.

By the way, we do stuff like this in the enterprise already. This is what we use e-mail and attachments for, this is why we use mailing lists and address books and spreadsheets and documents and presentations. All the things we’ve grown to love.

Or, in my case, hate. If you’re like me, you’ve had it with those tools. Absolutely had it. H.A.D. I.T. They are so not fit for purpose. Or. looking at it another way, there is a generation of tools out there that are so much more fit for purpose.

We’re not dealing with firehoses any more. We’re dealing with capillaries, as I discussed in my post yesterday. And these capillaries carry and distribute information nutrients, and process and eject information waste and toxins. The real power of all this lies in the increasing transportability of context.

Oh, incidentally, in the past, I’ve found the tools for grabbing screenshots frustratingly complex and time-consuming, so I’ve tended not to use them. It is fitting that this time around, I could do all this easily. Because of a project called Jing, and because I then had simple and seamless ways of going from Jing to Flickr to iPhoto to ecto to WordPress. And guess how I found out about Jing? Through someone’s tweet.

Also incidentally, it would be worth looking at the role played by the opensource movement in making sure we can move around so freely between all these applications. Which brings me to a strange conclusion. More a hypothesis. Am I right in considering the possibility that VRM is necessary only because everything is not opensource? That good opensource obviates the need for VRM? Doc? Don? Steve? Chris? Chris? Anyone out there?