It started with a tweet. Mark O’Neill, someone I’ve known for years, got in touch with me, to alert me about something. I trust Mark, I trust that when he sends me something to look at, it is usually worth looking at. Whatever it turned out to be.

So I went and took a look. It was a conversation on metafilter relating to a concert by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, at Wembley in 1974. Mark knew I was a fan of the group; he’d seen fit to spend time filtering the firehose for me, the least I could do was delve into the conversation. So I did. And that led to my finding this delightful gem:

A performance by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. And a fifth, somewhat unusual, member. Tom Jones. Initially I was a bit suspicious, not wanting to believe my eyes. I watched it, heard it, loved it. A fabulous version of Long Time Gone, one of my favourite CSN songs; I say this, bearing in mind that David Crosby songs are usually best when David’s doing the vocals. It seemed a bit odd that every copy of the video I could find had what appeared to be a Turkish incantation slathered all over it: Burc Arda GUL, with the original uploaded to a Youtube channel bearing that name. But he turned out kosher as well, tweeting as @arda1989, with a background that looked suspiciously like a photo of Tom Jones with Elvis. There is some reason to suspect that our man Arda is a Tom Jones fan.

But I was still not satisfied, so I cross-checked with Sugar Mountain and found the performance listed:

And there it was. 1969. 6th September. ABC Studios, Los Angeles. This is Tom Jones. With Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. Setlist You Don’t Have To Cry/Long Time Gone.

It’s a great song, sung by a great singer, accompanied by some fabulous musicians, one of whom wrote the song. But that’s not what this post is about.

What I wanted to share was the environment that made my finding it possible. The relationship with Mark. His knowledge of my interest in music. His choosing to share something with me. How simply and conveniently I could check out what he was sharing. The context that all this came wrapped in. And the availability of tools to be able to dig deep into that context, partly for curation, partly out of curiosity.

Serendipitously, I’d been thinking about music and its “wrappings” for a completely different reason. Stephen Bayley had written in the Times yesterday about the death (and life) of Storm Thorgerson.

Sadly that article’s paywalled. The part that you can see “free to air” starts with a humdinger of a quote: No one has ever loved a download.

Now that was something that’s been on my mind for some time now. Those of you who follow this blog regularly will know I tend to listen to my music on vinyl. I’m convinced the music sounds truer and “better”, that there’s more depth and clarity to the sound of music on vinyl when compared to digital music, even the so-called “lossless” stuff. [That may change: I am eagerly waiting to find out more about Neil Young’s Pono initiative; I had the privilege of meeting him personally, and it became clear that he was passionate about finding a way to make digital music sound a whole lot better than it does now.]

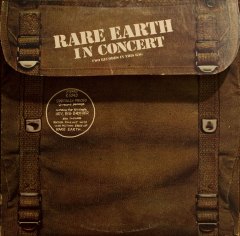

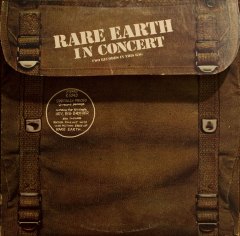

These were the covers of some of the albums that delighted me in my youth. And they weren’t just there to protect the vinyl. They were works of art to thumbtack on to a bedroom wall; they were repositories of learning, with encyclopaedic facts about the music, in terms of lyrics, line-up, instruments, credits, liner notes by vaunted critics, the lot; they represented experimentation in design: newspapers, knapsacks, 2D cuboids. When I bought an album for the first time, I would spend time savouring the packaging before allowing myself the sheer pleasure of placing the turntable arm on my Garrard gently on to the playing surface. [If you’ve ever been an Apple fanboy, you’ll understand the feeling. How taking the packaging apart is a time of reverence].

These were the covers of some of the albums that delighted me in my youth. And they weren’t just there to protect the vinyl. They were works of art to thumbtack on to a bedroom wall; they were repositories of learning, with encyclopaedic facts about the music, in terms of lyrics, line-up, instruments, credits, liner notes by vaunted critics, the lot; they represented experimentation in design: newspapers, knapsacks, 2D cuboids. When I bought an album for the first time, I would spend time savouring the packaging before allowing myself the sheer pleasure of placing the turntable arm on my Garrard gently on to the playing surface. [If you’ve ever been an Apple fanboy, you’ll understand the feeling. How taking the packaging apart is a time of reverence].

Serendipity surrounds so much of what I experience. So it should come as no surprise to you that I was going through all this at the same time as I was re-reading David Byrne’s fantastic new book How Music Works. [Another one to savour, in packaging and design as well as in content]. If you’re interested in music, go buy it now. It’s far more important than reading the rest of this post.

I’m not going to review the book here and now, other than to say I shall be buying many copies. And giving them away. And that’s something I do rarely, I’ve probably done it for a dozen books before. [They include The Little Prince; The Cluetrain Manifesto; The Social Life of Information; Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital; the list is not that long].

I’ll say this much: David Byrne provided me with a lot of insight into how context matters in music: context to do with performances and halls and acoustics, improvisation techniques, changing cultures and ways of listening, recording studios, technology, business models, and so much more.

Which brings me to what I really want to say:

For much of life, it has been difficult, sometimes impossible, to carry and preserve context alongside information.

Context matters.

The who, the when, the where and why. Identity. Location. Time.

The provision of context allows us to find out more about the information, to help us on our journeys to figure out meaning.

We live in an age where it has become easy to record an activity, to create a persistent record of that activity. Persisted as text, graphics, stills, audio, video. Persisted with metadata about source, time and place, with the tools to explore that context further.

Music just happens to be an easy place to draw analogies for all this, but the principles are becoming true for everything we do, in our personal lives as well as our professional lives.

We’re able to “quantify” ourselves, record so much of what we do, where we go, how we are. The quantified firm is upon us as well. With the ability to record so much, replay so much, analyse so much, understand the root causes of so much.

It’s easy to cavil and groan about 1984.

I live in 2013. I live in a world where past paradigms have managed to make social and economic divides worse, where the evil of povert, malnutrition and disease continues to affect billions; a world where challenges to do with health and nutrition and housing and hygeine don’t seem to be getting better; a world where over 9 million children of school-going age aren’t at school, and where the number of disaffected unemployed youth is measured in tens, if not hundreds, of millions; a world where resources like energy and water are getting scarcer, where our understanding of our interactions with our environment continues to be poor.

I live in 2013, a time when I am told that we may be at “peak longevity”, as diseases we’ve “conquered” return in powerful mutations, a world where obesity becomes the number one killer.

I live in 2013, a time when we have the technology to record and replay much of what we do, how we interact with the world around us; the ability to provide people with tools to make sense of that data by making the labels, the taxonomies, the low volatility categories and classifications, available to all at low cost; the ability to build platforms that make sensemaking easier, by connecting the reams of data, correctly classified, with platforms that make analysis and visualisation of the information easier for all.

I live in 2013. And I live in hope.

Like this:

Like Loading...