Note: This is the fourth in a series of posts I’m committed to writing about filters; I started with the principles of filtering, and will proceed to blow up each of the principles in as much detail as makes sense at this stage. Earlier I looked at network-based filters, and then spent time on routing. Today I want to look at something a little broader. I want to look at the issue of publishing responsibly.

Background

We live in a world where soon everyone and everything will be connected, one where everyone will soon be able to “publish”.

When I enumerated the seven principles of filtering, I took care to state that we should not design filters on the “publish” side, we should only design them to be used “subscribe” side. There are good reasons for this, mainly to do with avoiding “censorship by design”: we do not want to build structures that allow bad actors to dictate what everyone can see, read, hear. And if we design publish-side filters, that’s what will happen.

But there is still a case to be made for publisher-level filters, an exception to the rule. It’s a filter that most journalists are well aware of. It’s a filter that is quite different from any other filter I speak of, because it is not programmatic. It is code-based, yes, but it’s to do with the code we live by as human beings, rather than a set of instructions for a machine.

Publishing responsibly

Liberty is not licence. As the right to publish becomes universal, we have to perceive the right in the same way that we need to perceive any other universal right. The right comes with a duty, a set of duties. Duties that we owe to society in exchange for the right to publish. As I said earlier, this is something the world of journalism has needed to understand for centuries (even if it not always clear that they act according to that understanding. But that’s another matter).

When I started blogging back in 2002, I had to be very careful what I said and where, given my role and how that role was perceived. So the bank I worked for weren’t too keen on my blogging publicly; that didn’t happen till 2005. Since the audience was largely constrained to Dresdner Kleinwort folk, I wrote principally about work. Then, as things began to open up, I had to think about this whole area differently.

Initially I took the view that I would not share anything unless I could figure out whom it would help and how they could gain value from what I was saying. Between late 2005 and early 2007, I first went public-open with my blog, then started with Facebook, then joined Twitter as well.

As I learnt more about how these things worked, I began to refine my thinking about why I would share anything. And for some years now, this is where I’ve landed up:

Now I use a different test. Before sharing anything, I ask myself “Could this hurt someone?” And if the answer is yes, I hold my (digital) tongue.

How can we hurt others through what we share? Let me count the ways.

Not hurting others

Way 1: Make sure what you’re saying is accurate. Look for corroboration. Check it out. Where relevant, point to the source as well. Learn which sources to trust. Use your noggin, sanity-check it. It’s very easy to help inaccurate rumours circulate. There are also a lot of trolls about, looking to attract attention to themselves and to sensationalise as part of what they do, often with exaggeration and paucity with the truth. Think before you retweet them.

When I was at university, my namesake and erstwhile godfather, Jayaprakash Narayan, was known to have serious kidney problems; he spent a lot of time on dialysis. Which meant my colleagues used to have fun at my expense if I failed to turn up. Roll 7? Gone for dialysis, sir. And then one day it was reported that he’d died. The BBC World Service, no less. But he hadn’t. There was then a localised mini-rumour that I’d died, my personal Mark Twain moment. Why did this happen? It was because the BBC had said that JP had died. If it wasn’t the JP, then it must have been some other JP. And so the rumours began, albeit short-lived. With trust comes responsibility.

More recently, I had to learn this lesson again for myself. I saw reports that Michael Schumacher had been badly injured in a skiing accident, then read a story, from a reputable source, that his injuries, while serious, were not that serious. So I linked to that story. Soon afterwards it became clear that the reputable source was wrong, and I had to correct my earlier tweet.

Which brings me to another important point about accuracy. If for any reason you publish something that isn’t accurate, correct it as soon as you know that to be the case.

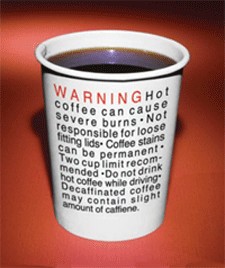

Way 2: Respect the audience and context. Think about who’s going to be reading what you publish. Okay, it’s get-on-my-high-horse time, please humour me. Take the term Not Safe For Work or NSFW. I’ve been bemused by this, sometimes even mildly needled. Is work the only place where the “not safe” label has meaning? Why isn’t there a not-safe-for-home? Or a not-safe-in-front-of-the-children? Once you go down that path, you will soon lead to a list of not-safes. Before you know it, someone will decide it’s a good idea and then (heaven forfend!) legislate for it. And we will land up with forced labelling of everything as not-safe-for-something-or-the-other. Warning. Contains Nuts. So before that happens, we need to start using some other signal. Something closer to “May shock or offend”, something simple that covers a whole litany of not-safes.

This is particularly important when it comes to use of images, especially those of the “graphic” variety. Today, more and more of the streams we live in now open up the image and display it as default. Not a good thing. As subscribers we should be able to turn that off. Which reminds me of another awful irritant. Web sites that burst into song without being asked. Puh-lease!

Fairy tales can be scary. Grandmothers turning into wolves. Parents abandoning you and sending you into forests in the dark. The reason that children don’t find such stories scary is because their own imagination stops them from dreaming up stuff that can really scare them. There’s a self-correcting mechanism there. That mechanism worked fine when the stories were oral. It continued to work fine when we moved to text and reading. Early illustrators stayed with the program and drew non-scary scary things. But nowadays we seem to forget all that. That’s a problem.

We should think about what we share and whether it has the possibility of being seen by someone who can’t handle it…. and then it falls upon us to prevent that happening. As individuals, not as society. As individuals using social conventions rather than through regulation. Here’s a simple example. A few days ago, I saw a video to do with spiders. It was fascinating, all the more so because I have no fear of spiders. But my wife would have nightmares if she saw the video. Which means I would do everything I can to ensure that she is not exposed to that video. That’s the sort of reason why films and games are age-graded and certified. So when we publish “in public”, in common space, we need to think about who else is able to see what we publish, and to show some responsibility.

Way 3: Don’t spoil things: There are very few things people now read, listen to or watch “live”. We have had the ability to Tivo so many parts of our lives for some time now. So people record things and replay them later. Catch-up services make this even simpler, by recording it for everyone and then making it available for a limited period for replay. We all know that this happens. So why do we bother to tweet or post stuff that has to do with TV programme contest results, sports results, film plots, book plots? Obviously there comes a time when it’s not that easy to avoid mentioning a “result”. But we have to learn how to do this safely. TV news stations have been using spoiler alerts for a while, where they audibly warn that a result is about to be flashed on a screen, given people the chance to look away if needed. IMDB provides spoiler alerts within film reviews, warning you not to click further unless you want to run the risk of having the plot exposed to you. We have to learn how to implement spoiler alerts as part of our sharing practice.

Sometimes the “spoiling” is subtler and your responsibilities are far more serious. You could be playing with other people’s lives. Now that everyone has a smart always-on alway-connected mobile device 24×7, every public event can be live-tweeted. Say you’re watching a hostage crisis play out. Be careful what you say because you could inadvertently tip off the hostage-takers and accelerate extreme and unwanted reactions. This is serious stuff. A couple of times as I watched what was being said, particularly on Twitter, I wished I could yell to the tweeter to cool it.

Summary

Those, then, are the three main ways we have to show responsibility in what and how we share. Of course we have to obey the law as well…. except when the sole purpose of sharing is to protest against the law…. in which case it is reasonable to break the law, knowingly, and to face the consequences. That’s not what I mean here. I’m talking about avoiding being racist or sexist or ageist, stuff like that. We should not be in the business of fomenting hatred by “sharing”. But that’s why we have laws. Sometimes those laws are asses, and deserve challenge. These are exceptions. The rest of the time, what we share should respect the laws of the land in which we do the sharing.

Views?

Here’s a visual, part 2, to explore the different options – https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/69746264/filters2.png

Joachim, thanks for the visual. Appreciate the help/

Much of publishing responsibly comes down to self filtering. Know some who are not comfortable doing this and so have cut themselves off from public transports (and the benefits which can accrue on them) in favor of only private forums where they feel they need not self filter (though they inevitably do to fit that particular domain, anyway.)

@jerome thanks. will you share more about the filtering service in days to come? is there somewhere we can find out more about it?